|

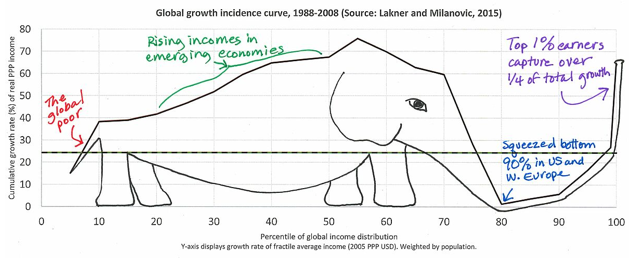

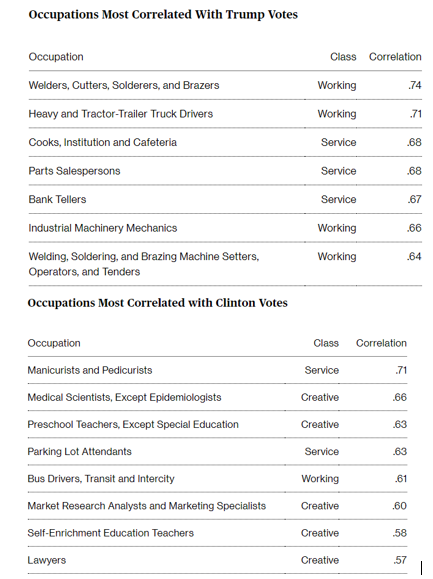

Nathan Newman Why did so many non-college whites lurch towards Trump in the 2016 and 2020 elections--and conversely why are more educated whites trending towards the Democrats?  any progressive analysts are a bit anguished at what they perceive to be an inversion of traditional class politics in voting, which for some means that the new split in voting has to be about cultural polarization, not class divisions. In a recent piece, “Class Politics: Its Return Is Nigh,” Seth Ackerman, who is executive editor at the socialist magazine Jacobin, complains that a crop of current Democratic pollsters and pundits - David Shor, Sean McElwee, Eric Levitz are named- are ignoring the importance of class in American politics. Ackerman is concerned that Democrats are not structuring their politics to appeal to voters’ class interests, but instead appealing to rich, suburban voters based on their “moral values” in what some pundits are assuming is a “post-materialist” world. If cultural issues are driving which political party people sort themselves into, then these Democratic pollster-pundits are just trying to divine the messaging that can cobble together a political majority--what has been dubbed “popularism” by many in that group. Levitz--whose leanings are sympathetic to Ackerman’s economics--challenges Ackerman on some points, but does agree that voters are generally polarizing based on cultural issues, but adds that many new non-college white Republicans then adopt conservative economic views by a kind of osmosis (or likely rabid Fox News exposure). Where I would differ from both Ackerman and the Shor-McElwee-Levitz camps is that I think we are currently in a period of class-based voting and party polarization unmatched in my lifetime and possibly in American history. On one side, we have a Democratic party more forthrightly demanding that the wealthy and corporations pay more, with approval of labor unions at a modern high point, and Dem leadership proposing trillions of dollars in spending for working-class families - even as the Republican party pushes tax cuts, union-busting and slashing spending on the unemployed and working families in the states they control. If political divisions were being driven by cultural differences, we would expect economic policy differences between the parties to be more muted, not accelerating in opposite directions. The Democratic Party is more homogeneously pro-labor than even during the New Deal and you see that in both voting patterns at the national level but also policy implementation in states Democrats control, as I detailed in this Alternet piece. So if the parties are polarized based on “cultural issues,” it may be because differing class politics and strategies are being dressed in clashing cultural clothes--not just the other way around. This cultural component of class organizing is a point Mike Davis focuses on in his recent essay, “Marx’s Lost Theory: The Politics of Nationalism” from his collection, Old Gods, New Enigmas. As Davis argues, Marx and many inheritors of his analytic approach didn’t mechanically assume that class politics flowed from the lowest-income members of a society embodying the most radical class politics--and there was therefore not automatic degradation of righteousness progressing up the economic ladder. Instead, as mass politics emerged in the 19th century, “secondary class struggles…over taxes, credit, and money are typically the immediate organizers of the political field. They are also the relays whereby global economic forces often influence political conflict and differential class capacities.” Marx himself at times highlighted the reality that the lowest-income peasants and the “lumpenproletariat” didn’t automatically land in the socialist-oriented camp for this very reason. Nationalism, prejudice, nostalgia are then taken up to garb changing class politics in the clothes of the past but with often very different economic motives shaping particular class coalitions. Without a doubt, racist cultural politics is driving much of U.S. politics in short-term political movements, particularly the Trumpist movements, but economic trends in the longer term have shaped and reinforced those racist and nationalist views. Putting US Working Class Politics in a Global Context How global forces have shaped the material basis of nationalism in our own politics seems quite relevant for understanding a Trumpist GOP movement with the slogan “Make America Great Again,” and whose top policies are focused on global product markets via trade wars and on global labor markets via anti-immigrant policies. Placed in a global context, the median income of American workers is 4.7 times as much as Chinese workers--and many times those in India, Sub-Saharan Africa, and many other countries, placing white American workers generally in the elite of the global workforce, whether non-college or college-educated. Assuming the non-college group with somewhat lower relative incomes is a stand-in for an imagined global proletariat is then unlikely to hold true. And neither group is homogeneous either in their voting patterns or other characteristics and, of course, the mass of non-white non-college-educated workers vote quite differently from their white non-college counterparts. But if we want to step back and understand what is shaping differential responses to the global economy, one key element is the pattern of global economic growth and the reactions of U.S. workers. The so-called “elephant chart” by economists Branko Milanovic and Christoph Lakner (with some illustration added by the FES Foundation below) highlights income growth for each income percentile on the globe, from the continuing extreme poverty at the very bottom to the quite rapid growth among emerging economies, particularly China, the extreme gains of the super-wealthy and, a particular point highlighted in blue, the stagnation of income for many workers of all educational levels, save the top elites, in Western Europe and the U.S. As Milanovic himself argues, these results are driven by the “defining dynamics of globalization: in the last 40 years, many jobs in Europe and North America were either outsourced to Asia or eliminated as a result of competition with Chinese industries.” Our Two Parties Reflect Two Class Strategies for Addressing Stagnating Incomes Experiencing this reality in their stagnating incomes, Americans could easily gravitate towards two targets to improve their own material conditions: either seek to expropriate some of the burgeoning growth among emerging economies or go after the wealth of the super-elite, the global top 1% holding 43% of all global wealth in 2020. Arguably, our two political parties have increasingly sorted themselves along the line of those two strategies, although there are obviously contradictions within each party. On one side, you have workers who have found themselves directly in competition with developing world workers. They have allied with a portion of the economic elite willing to help them extract some additional income and jobs from those emerging economies, including via trade wars, energy policy, agricultural policy, and other economic and occasionally military actions, all in exchange for support for the Republican Party policies that help that elite keep their wealth. On the other, you have a base of workers whose industries are largely outside global competition, such as service work or public employment, or in what has been dubbed the “creative economy” where US advantages in exports are based on public investments in education and other public goods. For these voters, the key strategies for improving their own economic status require extracting some of the income of the economic elite—many of whom pay domestic taxes here in the U.S. - whether through stronger labor rights, tighter economic regulation, or higher taxes paid to fund government spending. Those pro-labor policies keep a portion of the industrial sector’s workers, particularly those who still see some room to maneuver for extracting higher wages from their employers, in the Democratic Party camp as well. And when you look at voting patterns based on occupation, and their relationship to their dependence on global manufacturing competition, as this study by researcher Richard Florida highlights, this polarization seems all the clearer. The higher the percentage of welders, machinery mechanics, parts salespersons, and other jobs tied to the manufacturing and trade-in-goods economy, the more likely that state voted for Trump. And the higher the percentage of manicurists, medical scientists, pre-school teachers, transit drivers and many others tied to non-manufacturing professions, the more likely that state was to support Clinton in 2016. In the study, service workers overall were a mixed bag politically, no doubt reflecting other studies showing people’s views on trade policy and related issues often relate to the dependence of the region where they live on trade as much as their own employment. For this reason, as service work continues to become an increasing part of the workforce, the “white non-college” category will still be up for grabs politically. This is also why so much of new union organizing that has occurred in the last few decades has been among service workers, including janitors, home health aides, hotel workers, as well as increasing efforts to organize large-scale retail like Amazon. Reinforcing the march of educated voters into Democratic ranks is what could be called the “proletarianization” of the professional and creative classes. The increasing disappearance of small firms and the centralization of bigger firms means there are far fewer opportunities for such professionals to have an ownership stake in their workplaces, meaning they are far less likely to identify with the ownership class than in decades past. Even doctors are increasingly just employees of medical services chains. 2018 was the first year more doctors were employees than in the management of their own firms and this is just accelerating with 70% of physicians under age 40 now being employees. In sync with this change, doctors have moved from being a heavily Republican-donating group to increasingly supporting Democrats, with employment status being a key variable in studies documenting this shift in political loyalties. That same corporate consolidation has driven increased union militancy in the news media, in sports, and in Hollywood- as even some of the highest paid employees in creative fields find their politics directed into more anti-corporate directions. Trade and Cultural Politics Attitudes on race end up closely tied up in voters’ views on trade, again emphasizing that “culture” and “class” affiliations are not so separate. As an analysis by the Peterson Institute’s Marcus Nolan detailed, white voters in regions with employment impacted by the “China shock” seemed to adopt “harsher attitudes towards immigrants and racial minorities” and even to gravitate towards more fundamentalist versions of Christianity. What this means is that conservative racial and religious views may influence workers to gravitate to a set of policies hostile to non-white workers around the world, but it also seems to be true that gravitating to a trade war mindset may encourage more conservative cultural beliefs. That kind of nationalist framework for economics may encourage a more racist approach to other policies as well. Notably, campaign ads on trade overwhelmingly portray victims of bad trade deals as being white--and in fact, studies show that when trade victims are shown as being non-white, white voters are less supportive of trade interventions. So a trade war framework and racist cultural politics become self-reinforcing in our politics. On the flip side, Black and Latino Americans are far more favorable towards trade, despite often personally being vulnerable to the vagaries of global trade. Partly as the linked survey shows, Blacks and Latinos are less likely to adopt a nationalist framework towards trade or claim the U.S. is superior as a country, reflecting the interaction of cultural frameworks and class politics. Latinos notably have the highest enthusiasm for trade, possibly reflecting their greater connections to family and workers in other countries. The Geography of our Economic and Cultural Divide Culture, race, and class intersect in the geography of the exurban communities where global outsourcing has left towns built around a single company factory in steep decline. These communities were often created in an earlier generation of outsourcing, when companies fled unionized cities, de-industrializing heavily black urban areas as scholars like William Julius Wilson detailed. Some of the firms that left succeeded in escaping their unions while in others, workers managed to maintain them--but the racist politics of suburbanization meant most of those factories ended up in far more homogeneously white communities in smaller towns and exurbs than the racially diverse urban centers they left behind. So when the globally-induced de-industrialization of more recent decades came, the communities experiencing those losses and the culture of those trade-induced grievances were more homogeneously white as well. Scholars Case and Deaton have detailed the rising despair, opioid use, overdoses, and suicides that raised mortality rates among older whites in such communities in recent decades and, as I detailed in this piece, a chunk of Trump’s support was driven by alienated whites in those communities: Reflecting another measure of alienation, Trump received the most votes from communities where opioid addiction was highest, according to one study. Even accounting for demographic and socioeconomic measures, the voting map showed significant voting correlations with opioid use. "When we look at the two maps, there was a clear overlap between counties that had high opioid use ... and the vote for Donald Trump," says Dr. James S. Goodwin, chair of geriatrics at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston and the study's lead author. This fits another study finding higher rates of illness in general was correlated with Trump’s vote, MORE than even educational differences in the population. As we look towards economic strategies for the future, the reality is that large swathes of Trumpland don’t have much of one economically. Communities were built around single factories, extractive industries nearing exhaustion, and other monocultural economic enterprises without many options for local economic alternatives. A destructive aspect of the fragmentation of American manufacturing into exurbs and small towns is that it was unable to respond effectively when emerging economies added new competition. Vibrant industrial districts in places like Germany and Italy, where industry clustered together in historic urban regions, were able to retool their approaches and kept roughly 20% of their working population in manufacturing jobs. (See Piore & Sabel and Michael Best for more on other nation’s responses to the new manufacturing competition) US factories, geographically cut off from each other and from broader urban resources, just shut down at far higher rates, leaving the United States with only 10 percent of its workforce in manufacturing, half the percentage of Germany and Italy. This lack of economic innovation means the 2,564 largely rural and exurban counties that voted for Trump in 2020 produced just 30% of our nation’s GDP, while the 520 mostly urban or inner-ring suburban counties that voted for Biden produced 70% of our GDP. The systematic weakness in their local economies means promises to transition to new industries sound hollow to many Trump voters--because they largely are. New industries need a supportive set of services and interlocking supply networks that only urban regions can generally sustain. Given their economic flexibility, Democratic-leaning urban areas can far more confidently expect that investments by a well-funded public sector can produce new jobs to replace any potential losses threatened by corporate elites if their taxes are raised. On the other hand, the desperation of workers in Trump regions to hold onto their remaining industries at all costs, given the unlikelihood of their replacement with comparable jobs, makes their politics of collaboration with those corporate elite more understandable, even if futile in the longer-term. Throwing their lot in with their corporate employers in a nationalist showdown against emerging economies - and against their local political stand-ins, immigrant workers, seems their only option. The Cultural Politics of Nationalism Which brings us back to Mike Davis on Marx’s cultural politics of nationalism. Many have tried to cite past leaders who Trump resembles, authoritarians of various stripes, and fascists like Hitler or Mussolini. But in many ways, the most precise predecessor for Trump was the original prototype of the modern democratic authoritarian leader, Louis Napoleon, the man who, out of the turmoil in France of 1848, would win the Presidential election that year and would stage a self-coup in 1851 that would make him emperor of France until 1870. Much as Trump claimed the goal of “Making America Great Again,” so too Louis Napoleon promised to restore the glory of France that his uncle Napoleon Bonaparte had brought the nation. In the 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Marx saw Louis Napoleon as representing the class interests of the broad peasantry of the nation, albeit the conservative aspirations of those in the peasantry that had been pauperized by “mortgage debt burdening the soil of France [in] an amount of interest equal to the annual interest on the entire British national debt.” Their desperate economics, in Marx’s words, and “historical tradition gave rise to the French peasants’ belief in the miracle that a man named Napoleon would bring all glory back to them.” Thus, the growing urban proletariat would find itself at odds with voters in rural France, who would turn to an authoritarian leader in the fruitless hope of stemming their economic liquidation through restoring national glory. Sound familiar? As Marx said then, history repeats itself, “the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce” - with the farce compounded with Trump and his movement today, as QAnon, the threat of “Critical Race Theory” and other conspiracies stalk our modern politics. But the core is that real economic concerns and class-based strategies, however misguided, underlie the political alliances of our politics. The cultural politics of nostalgia and racism and antediluvian gender politics derive from and reinforce that divide. We in no way are in a “post-materialist” era but are in one where the economic “fear of falling” in the words of Barbara Ehrenreich, consumes our political lives. The threat of overseas competitors in the developing world and of immigrants taking our jobs is ever-present as a cudgel for demagogues to wield. How to Move Forward How to address this in the short-term will be debated by the pundits, but given how deep-rooted this polarization clearly is, any tactical messaging strategies will make changes in voting patterns only at the margins. For the immediate 2022 or even 2024 election cycles, I’m honestly unsure whether the strong left “Medicare for all/Green New Deal/Go Big” or the David Shor-style carefully-selected-popular-issues approach is most likely to win in swing districts. But we aren’t going to fundamentally change our politics if we argue just over messaging because we need to win over a large super-majority of the population to make the fundamental changes we need. We need those super-majorities to overcome the dysfunctional, anti-democratic structures of our political system, from a deeply unrepresentative Senate to a Supreme Court hostile to any progressive advance to state governments captured by rabid right-wing ideologues implementing gerrymandering across the nation. But we also need to reach and convert some of that Trumpist voting core because defusing the toxicity of despair and the ensuring racist alliances with elite interests is needed to overcome that corporate power. We also need a super-majority of the population to see a shared interest in not just working together in the United States but in seeing how the gains from combining efforts with other workers around the globe can confront that elite and redistribute power and income to everyone in the world, so that people are not perpetually pitted against each other - as happens not just here at home but in countries and between countries around the world. We need a long-term progressive strategy and it starts with going beyond trying to move people in one election cycle but doing the deep organizing, the building of human relationships within communities that can actually change who people are and how they see the world. As I argued in Organizing the Alienated: Take the Skinheads Bowling- to the Union League, the most effective route to this is in investing in union organizing in workplaces across the country, particularly in deep-red areas. As I noted, if progressives could waste $103 million on the no-hope Senate campaign of Amy McGrath in Kentucky, they should be able to find the funds to support new organizing campaigns and contribute to strike funds at a similar level. The payoffs won’t come in a single election cycle but we have long-term evidence that workers brought together in labor unions tend to become less racist and more able to see the gains from strategies “punching up” at the elites rather than punching down. Progressives need to organize as well around a global alternative to the trade war/anti-immigrant appeal to Trump working-class voters. Without a fundamental alternative to that in the public debate, it will be nearly impossible to convince many workers facing global competition that joining a progressive coalition delivering a bit more in public spending is worth risking their jobs. Twenty years ago during the battles against the pro-corporate WTO deals being negotiated in Seattle and beyond, progressives began to make inroads in that goal, building the “Teamsters and turtles” alliance that saw a path to environmental preservation, job rights, and global justice as an alternative. But those efforts were largely blown apart following 9-11, notably by a nationalist fervor stoked by conservative forces that rightly saw a nationalist framework as more favorable for their corporatist class alliance strategies. The corporatist trade deals negotiated by both Republican and Democratic Presidents have clearly failed most American workers, as evidenced by both the broad-based wage stagnation many faced but also by the acceleration of gains from trade accruing to the economic elite--all of which opened the door for Trumpist racist nationalist appeals around trade. Most of those recent trade deals focused less on lowering tariffs, the traditional focus of trade deals, and more on restricting local consumer and environmental protections through strengthening the power of corporations to challenge local laws through new “investor rights” provisions. Too often, intellectual property rights have won out over worker’s rights in such deals, a prime area where “creative class” alliances with corporate interests have been interwoven with Democratic Party-allied interests in such deals. To their credit, majorities of Democrats in Congress began voting against most such deals beginning with NAFTA and we have seen the glimmering of new approaches, such as strengthening labor rights that have been implemented in a few recent deals. The AFL-CIO and House Democratic leaders endorsed the NAFTA II agreement after they pushed successfully to include significant pro-labor changes adopted that at least improved NAFTA compared to the status quo. But Democrats need to present a far clearer progressive alternative on trade and global cooperation to both Trumpist trade wars and failed corporatist “free trade” that challenges enrichment of the global elite and delivers better jobs to workers at home and abroad. Biden has made the right moves in making workers rights the core of his official trade agenda and, probably, more importantly, hiring Thea Lee, the former President of the Economic Policy Institute and chief economist on international issues for the AFL-CIO before that, to oversee international affairs for the Department of Labor, which includes responsibilities for enforcing labor rights under trade deals. Biden’s global deal with 130 countries to establish a minimum corporate tax is potentially the most game-changing achievement on building a vision for global equity. Not only will it encourage more revenue for social spending around the globe, but it will also reduce the “race-to-the-bottom” tax competition between countries that also feeds job competition and flight to lower-wage, lower-tax jurisdictions. This is one of the few global deals in history purely dedicated to reining in the wealth of the corporate elites--and can ideally be promoted as the model for future global deals on other fronts to achieve the same goal. With such a global framework for long-term global cooperation to preserve jobs and redistribute growth from the elite to workers globally, then and probably only then, progressives can make the pitch to pull at least some of the Trump-supporting voters away from the nationalist trade war framework that keeps them in alliances with the Republicans. Where their industries are still viable, progressives should promote spending to keep them that way and for other workers, progressive need to provide jobs in viable transit-accessible urban-suburban areas that are both economically and environmentally sustainable--and build-in job guarantees to make any locational leaps seem less daunting for people who will understandably be reluctant to leave their existing community supports without such job guarantees. None of this is easy. None of this is quick. All of it has to be done amid vote suppression and the violent threat of fascist liquidation of our democracy all too present and all while addressing the critical needs of existing Democratic constituencies. But we need to do the deep personal organizing in red areas, particularly through new labor organizing, to address these fundamental economic issues structuring class alliances if we are to escape the toxic cultural conflict that they help drive. Just because the 18th Brumaire is Marx’s most quotable work, I’ll end with a line from his introduction which captures the frustration he and others had in facing down the nationalist prejudice that had brought Louis-Napoleon to power: “The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.” While Marx wanted the workers of the world to unite, he recognized that fighting through that cultural baggage of the past made it a hard slog. But there are paths to do it but we need to adopt long-term strategies to build the solidarity against the global 1% that can also topple the Trumpist nationalist fervor at home that cripples our current politics.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Principles North Star caucus members

antiracismdsa (blog of Duane Campbell) Hatuey's Ashes (blog of José G. Pérez) Authory and Substack of Max Sawicky Left Periodicals Democratic Left Socialist Forum Washington Socialist Jacobin In These Times Dissent Current Affairs Portside Convergence The Nation The American Prospect Jewish Currents Mother Jones The Intercept New Politics Monthly Review n+1 +972 The Baffler Counterpunch Black Agenda Report Dollars and Sense Comrades Organizing Upgrade Justice Democrats Working Families Party Poor People's Campaign Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism Progressive Democrats of America Our Revolution Democracy for America MoveOn Black Lives Matter Movement for Black Lives The Women's March Jewish Voice for Peace J Street National Abortion Rights Action League ACT UP National Organization for Women Sunrise People's Action National Network for Immigrant and Refugee Rights Dream Defenders |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed